Fricke’s Picks: Dylans Basement Bash

“At 2:12 Dylan plays a tender if slightly clumsy lead guitar solo on his acoustic twelve-string. At 3:18 Bob bumps his guitar on his chair.”

“At 2:12 Dylan plays a tender if slightly clumsy lead guitar solo on his acoustic twelve-string. At 3:18 Bob bumps his guitar on his chair.”

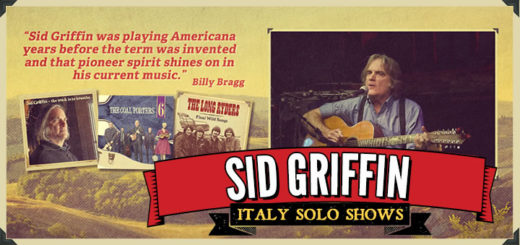

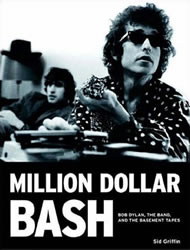

That is the kind of detail you’re in for when Sid Griffin gets to the track-bytrack heart of his book Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, the Band and the Basement Tapes (Jawbone Press). But Griffin, a singer-guitarist who has played Dylan songs with the Long Ryders and the Coal Porters, is a soulful detective who frames his colorful, precise descriptions of every circulating performance from Dylan’s 1967 Woodstock sessions with revealing context: Dylan’s daily creative life in retreat after his 1966 motorcycle accident, the brilliant shoestring engineering by the Band’s Garth Hudson, the evolution from alcoholic boys’-club fun on the early reels to the home-brewed majesty of “Tiny Montgomery” and “I’m Not There (1956).” If you don’t have the bootlegs in full already, Griffin’s sharp, witty analysis and articulate passion will get you hunting.

More reviews of Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, The Band, and The Basement Tapes

COFFEE, BEER AND MUSIC FOR THE SOUL

Friday , April 11 , 2008

Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, The Band, and The Basement Tapes

By Sid Griffin, Jawbone, $16.00

This is the story of allegedly 37 tape boxes, each comprising a seven-inch reel of recording tape. Every reel carries 20 minutes of recording time. Not all of them are full. Five (later six) men — Bob Dylan, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson, and Levon Helm — recorded the songs in Woodstock in 1967. At first, Dylan did not release these “revered” yet “misunderstood” recordings commercially. His fans and music-lovers heard them mostly as cover versions. For Sid Griffin, the author, these songs represent the American Sound. For the world, they are a venerated musical collection known as The Basement Tapes.

Griffin is aware that a story about a set of music tapes, however idolized, would sound out-of-key to the lay reader. He tries to guard himself against the peril by weaving into the plot nuggets about famous people, places and history. Thus, Million Dollar Bash does not start with the year of the recordings. Instead, it rewinds to Woodstock in the early 20th century to provide what Griffin says is the “necessary back-story”.

Woodstock’s fame as an artist colony was aided by its location and history. The town balanced the demands of art and commerce — providing actors, painters and musicians with a much-needed refuge to work freely and peacefully. What they produced could then be sold at near-by Manhattan. Dylan, who grew up in the bleak Iron Range Town of Hibbing, and was fond of cinema, painting and Robin Hood as a child, first visited Woodstock in 1963, when he was in his early twenties. He grew to love its small-town charms (“a hip Hibbing” he called it), and discovered that Woodstock could shelter him from his burgeoning fame. Two years later, Dylan and his wife, Sara, purchased Hi Lo Ha, a sprawling 11-roomed house on Camelot Road. Its Red Room was where the first recordings of the Tapes took place.

The Basement Tapes wouldn’t have happened without Woodstock, and a motorcycle accident. “Backbeat”, a crisp and delightful chapter in Griffin’s book, offers glimpses of Dylan’s early career as well as bits and pieces of Sixties America — the social and politic unrest, protest music and Vietnam. In the course of five years — from 1961-66 — Dylan transformed himself from a fresh-faced, ambitious artist to the spokesman of a generation, and then again to the poster-boy of rock ’n roll. But a demanding musical career sapped his creativity, forcing him to take some time off. So, on a July morning, even as Dylan rode his favourite Triumph motorbike, he happened to look up, into the bright light. The bike crashed and hurtled him through the air, scenes from his life flashing in front of him, as he recalls later.

As with everything else in Dylan’s life, the accident remains shrouded in mystery and speculation. Some say that he had suffered minor injuries. Others swear that he had almost died. Griffin, it seems, covertly sides with the former view. An injured Dylan, he writes, was taken to Dr Thaler’s house, an hour’s drive away, where he recuperated for six weeks. Those six weeks were a turning point in Dylan’s life, changing the man and his music forever.

The year after the accident, Dylan was joined by Robertson and, eventually, by the other Hawks at Hi Lo Ha. There the men, over strong coffee and Canadian beer, decided to make “music for themselves”. What emerged during these relaxed and informal sessions over an entire year were the songs, some of which have been included in the official album. The recordings took place mostly at two venues (The Red Room at Hi Lo Ha and, later, at the Big Pink) and were discontinued on no less than five occasions. Yet, this was one of the most productive phases in Dylan’s career: he would record almost 107 originals as well as 32 cover versions of some of his favourite artists, many of which (according to Hudson) were “barely written in the clinical sense of the word”. The world was shut out and the amps lowered, dead-lines were not kept and the phone went unanswered. As the seasons changed across the Catskills, Dylan and his friends continued writing, rehearsing and recording, producing such classics as “This Wheel’s on Fire”, “Tears of Rage” and “Santa Fe”. Along with their mentor, The Hawks evolved musically, taking the first steps towards becoming The Band.

Griffin, a solo performer and record producer, offers an insightful account of nearly all the music that was produced in the summer of ’67. For each song, he provides the title, as well as other details like the names of composers and the duration of the recordings, who played which instrument and so on. What he also presents is a rich and instructive analysis of the pathbreaking music. Griffin’s narration is lively. He peppers his analysis of the Tapes with witty anecdotes. For instance, this is Griffin’s account of the composition of “I’m a fool for you”: “At 1:03, Dylan calls out for a D chord and Hudson hears it as C, and Manuel hears it as a B”. They played on nonetheless, and a new day broke outside by the time the confusion was set right.

There are also equally detailed accounts of the making of the songs that The Band produced with and without Dylan, as well as the various cover versions of the Tapes by other performers, right up to the release of the official two-LP set by Columbia Records in 1975. The last chapter records the views of the likes of Al Kooper, Steve Earle, Robbie Robertson and John Hammond Jr. on the Tapes. The cheeky last entry is, aptly, a note from Dylan’s office. It goes like this: “Sid, my friend — Bob just doesn’t want to talk about it.”

Griffin’s skills as a writer are overridden by his considerable knowledge of music and of Dylan. But those looking for the man rather than the music will be disappointed by this book, in which Dylan, who once played a movie character called Alias, remains elusive as ever. That does not take anything away from Griffin’s painstaking research, which unravels little-known facts about these musical sessions. But this, in a way, proves to be his undoing as well: the reader’s mind could sometimes be numbed by too much detail, giving an obsessive edge to his meticulousness. Those who have little interest in Dylan or the Tapes, but are generally interested in music, could end up finding Griffin’s work tedious. Million Dollar Bash, like Greil Marcus’s Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes and many more before it, attempts to give the Tapes their due place in musical history. It is perhaps best to move on and leave unsaid whatever little there is left to be said. Dylan, for one, wouldn’t mind.

UDDALAK MUKHERJEE

from The Telegraph – Calcutta, India

April 2008